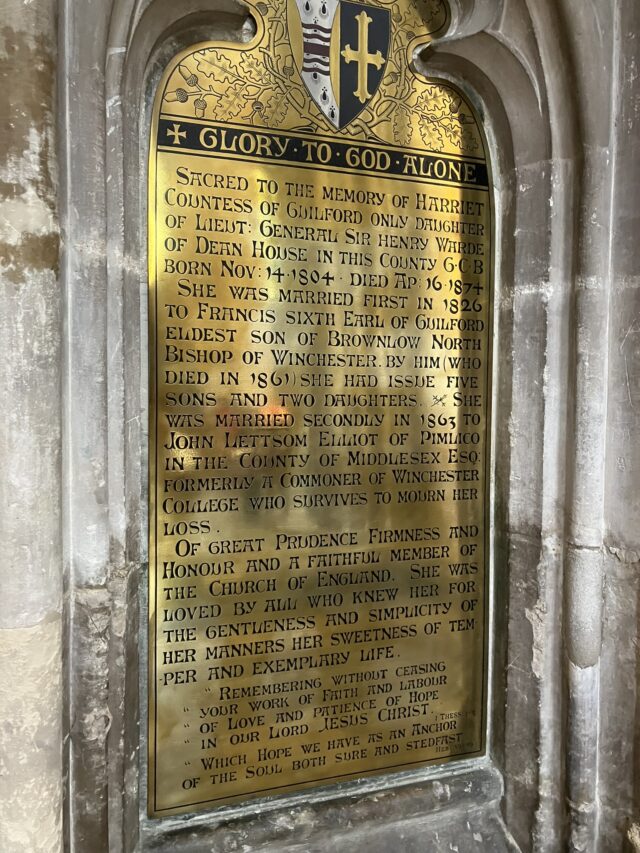

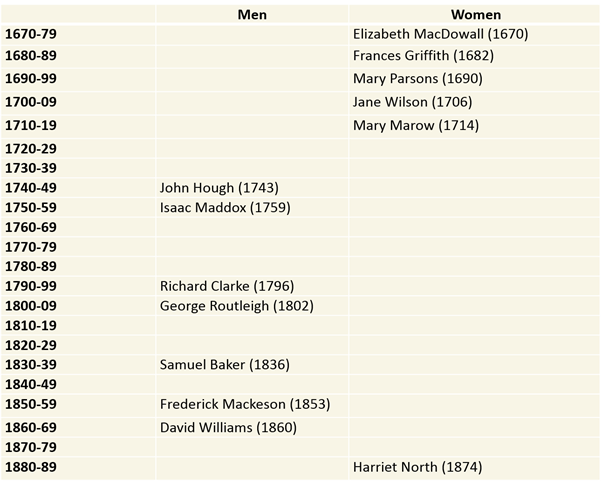

“Of great prudence, firmness and honour and a faithful member of the Church of England, she was loved by all who knew her for the gentleness and simplicity of her manners, her sweetness of temper, and her exemplary life.” Thus runs the epitaph of Harriet North, Countess of Guilford. “Prudence” (obscured by the reflection in the brass) is worth dwelling on. This classical virtue appears thirteen times in the records, at fairly regular intervals from 1670 through to 1874. If there is any change over time, it is in the sex of those it is ascribed to: before 1720, they are all women; after that date (with the exception of Harriet) they are all men. This chart shows the change.

Why this sea shift? I’m not sure exactly, but I suspect it has some connection with the declining importance of the household as a unit of production. In the seventeenth century, a wife of the upper class would be expected to “look well to the ways of her household”, as the Book of Proverbs puts it – manage the books, look after tenants, and so forth. “Prudence” was one of her essential attributes. But over the course of the eighteenth century, as managers took over the running of grand estates, the wife’s role was confined to that of companion and support to her husband and children. Tenderness, sweetness and love were now the virtues required of her, not prudence. Prudence became a masculine quality, something hard, dry and self-seeking – as it still is today.

Why Harriet North is the exception to this general rule, I cannot tell. It may be because because she outlived her very much older husband, Francis North, 6th Earl of Guilford (1772-1861) by thirteen years, marrying again two years after his death to a John Lettson Elliot of Pimlico. That suggests some degree of “prudence” and “firmness”.