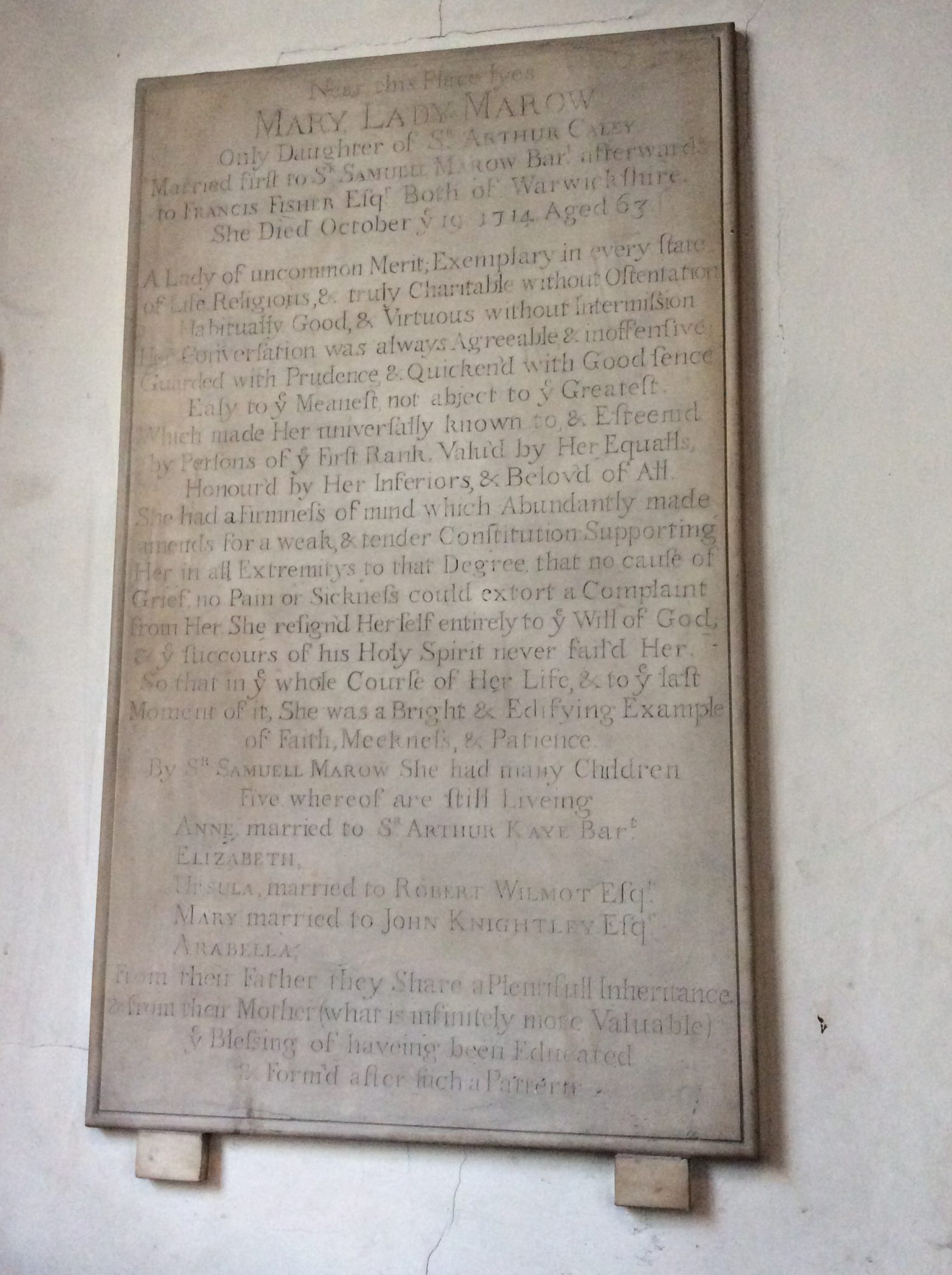

This epitaph, from St. James’s, Westminster, illustrates many of the qualities which a grand lady of the early eighteenth century was expected to possess. Lady Mary is said to have behaved with dignity to both superiors and inferiors; she was “easy to ye meanest, not abject to ye greatest”, which made her “esteem’d by persons of ye first rank, valu’d by her equals, honour’d by her inferiors, & belov’d of all.” Kindness to social inferiors – or “condescension“, as it is sometimes called – is praised on five epitaphs, the last of them carved in 1835, after which more democratic attitudes prevail.

Lady Mary is also said to have possessed a “firmness of mind”, supporting her in all extremities so that “no cause of grief, no pain or sickness, could extort a complaint from her”. The virtues of patience, fortitude and resignation in the face of illness and death are frequently praised on Georgian and Victorian epitaphs, particularly in connection with women, to whom no other form of courage was available. A search of “virtues of endurance“, as I have called them, brings up 55 out of 527 epitaphs. 29 of these are of women, which given that men in general outnumber women by more than two to one means that women were much more likely than men to be praised for these particular excellences.