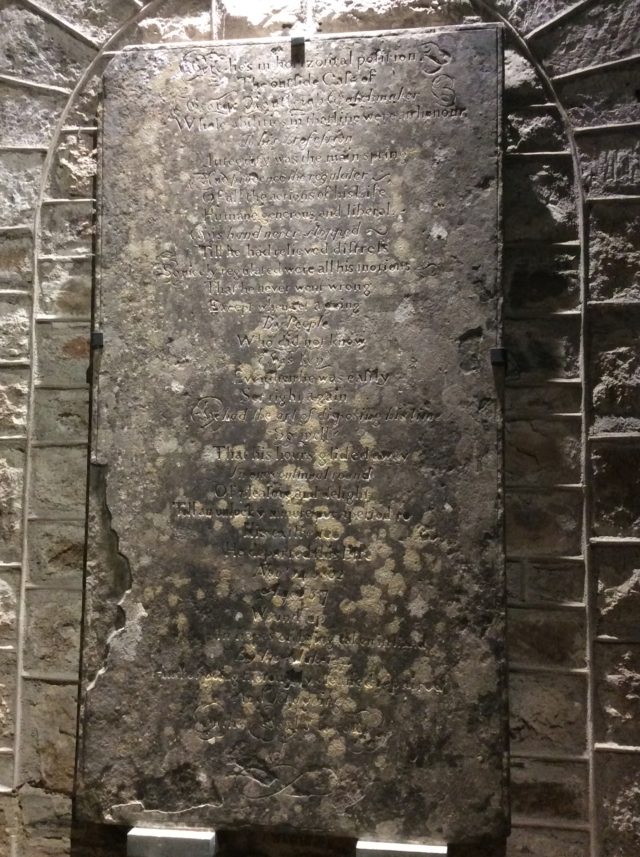

This epitaph for George Routleigh, watchmaker, is one of the main attractions of the little Dartmoor church of St. Petrock’s. The stone is eroded (it has only recently been moved inside the church, to preserve it) so here is the text in full:

Here lies in the horizontal position The outside case of George Routleigh, Watchmaker, Whose abilities in that line were an honour To his profession: Integrity was the main-spring, And prudence the regulator Of all the actions of his life: Humane, generous and liberal, His hand never stopped Till he had relieved distress; So nicely regulated were all his movements That he never went wrong Except when set-a-going By people Who did not know his key; Even then, he was easily Set right again: He had the art of disposing of his time So well That his hours glided away In one continual round Of pleasure and delight, Till an unlucky moment put a period to His existence; He departed this life November 14, 1802 Wound up, in hopes of being taken in hand By his Maker, And of being Thoroughly cleaned, repaired and set-a-going In the World to come.

It seems that George Routleigh was not the first watchmaker to be memorialised in this way. The same epitaph was printed in the Derby Mercury in 1786, and then again in the 1797 almanac of a black American astronomer from Maryland called Benjamin Banneker. So the joke had been “going the rounds”. I have one other example in my collection of the same kind of humour, this one concerning a shorthand clerk called William Laurence, who died in 1621:

Short hand he wrot, his flowre in prime did fade, And hasty death short hand of him hath made. Well couth he numbers, and well mesur'd land, Thus doth he now that ground wheron you stand Wherin he lyes so geometricall. Art maketh some but thus will nature all.

Perhaps there are other examples, but I haven’t found them. To us, these elaborate conceits upon the deceased’s trade seem in rather dubious taste, but they clearly didn’t strike people that way at the time. Death – or at least the death of clerks and artisans – was once a suitable occasion for wit.