Hannah Twynnoy, a barmaid at the White Lion Inn, Malmesbury, has the curious distinction of being the first person in England to be killed by a tiger. A local historian later recorded the incident as follows:

To the memory of Hannah Twynnoy. She was a servant of the White Lion Inn where there was an exhibition of wild beasts, and amongst the rest a very fierce tiger which she imprudently took pleasure in teasing, not withstanding the repeated remonstrance of its keeper. One day whilst amusing herself with this dangerous diversion the enraged animal by an extraordinary effort drew out the staple, sprang towards the unhappy girl, caught hold of her gown and tore her to pieces.

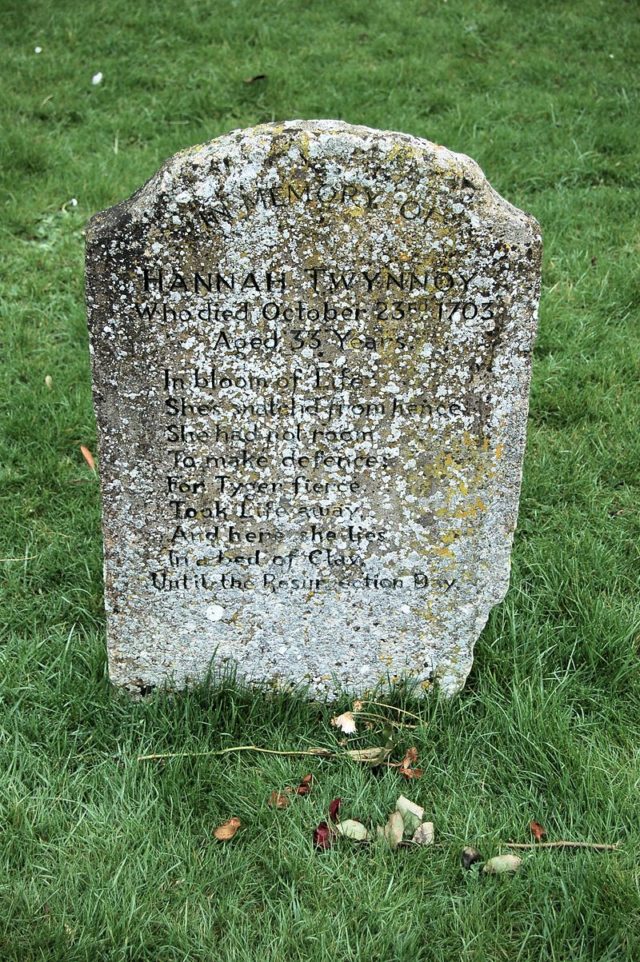

Hannah’s tombstone stands in the cemetery of Malmesbury Abbey. The poem on it reads:

In bloom of life She’s snatch’d from hence She had not room To make defence; For Tyger fierce took life away. And here she lies In a bed of Clay Until the Resurrection Day.

The doctrine set forth so artlessly here is that of the “resurrection of the body” mentioned in the Creed, according to which the soul will be reunited with the body on the last day. The same doctrine features on a few other early tombstones too. “Her soul resteth with God till the general resurrection when she shall rise again” runs the epitaph of Elihonor Sadler (d. 1622). “Here lyeth deposited his mortal part untill it shall bee raised up unto immortal life and glory”, proclaims the inscription on the tomb of Sir Nicholas Martyn (d. 1653). This ancient belief seems to have faded away during the Age of Reason. On late eighteenth-century tombstones, bodies no longer “rise up” out of “beds of clay”; rather souls are “translated” or “wafted” to their divine abode, to be received by the “angelic quire”. Heaven has become a matter of poetry, not fact.